This blog grew out of my fascination with political ephemera -- t-shirts, posters, pamphlet and graffiti -- from the post-colonial period in Africa, but also out of a real concern for its preservation. While there are archives of colonial-era material and growing digital collections of anti-apartheid material, less attention has been paid to the material culture of post-colonial political movements. Yet historians are increasingly researching the post-colonial, and we're seeing a 'cultural turn' of African political scientists on both sides of the Atlantic.

But what sources do they use to conduct this research? And will those sources still exist in 30 years time?

|

| An iconic TAC t-shirt. Will future generations appreciate how radical this shirt was? |

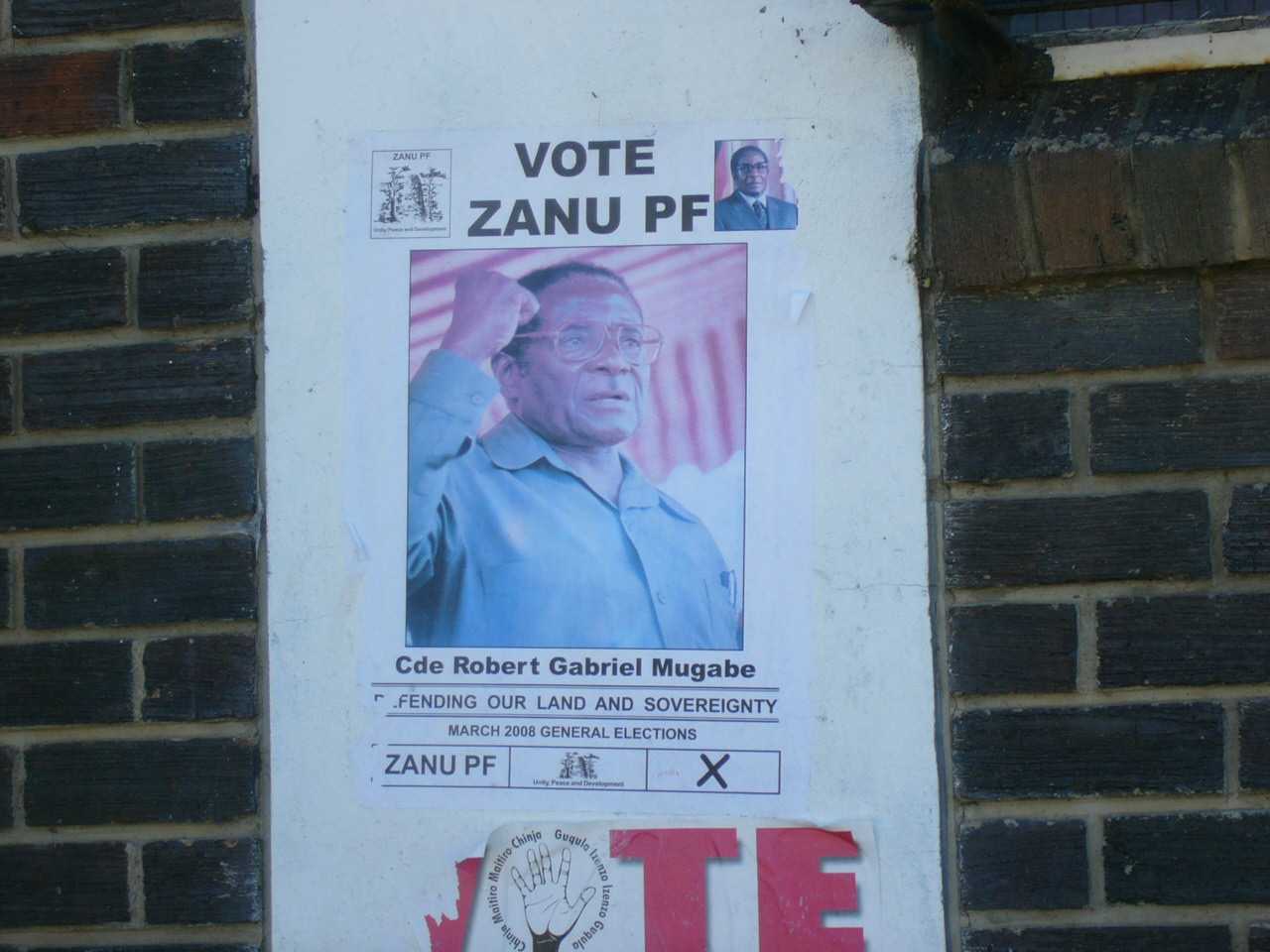

Political reform movements, NGO campaigns, and exhortation aimed at voters,

drinkers, and those at risk of contracting the AIDS virus to change their

behaviour have all contributed to shaping Africa's public sphere.

The material culture of

these movements is ephemeral – posters, pamphlets, and t-shirts are rapidly

consumed, but rarely preserved, despite it having much to tell us much about

its producers and intended recipients.

I'm hoping that this blog will contribute to protecting and preserving some of this material, with a view to enabling contemporary

researchers, future historians, and the interested public to gain a richer and

more diverse understanding of Africa’s public life than that often portrayed on

screens and newspapers in the West.

In much the same way as explorers, colonial officials and

missionaries brought back items of cultural and historical worth, which became

part of the museum collections in the UK , so new generations of

activists, VSO co-operants and researchers have brought back small but significant

pieces of African political history - sometimes in their wardrobes, but increasingly on data sticks, camera memories, and mobilephones.

Although not ‘looted’ in the fashion of previous generations, the

T-shirts, pamphlets and posters of contemporary Africa need to be preserved

and made accessible to students, researchers and the wider public in Africa and

elsewhere. In this way, the work of

political activists can receive recognition and be celebrated for its

creativity, humour and incisiveness, while also contributing to scholars' understanding of the period.

So, my hope is to encourage more thinking about the preservation of these materials - whether digitally or through more formal archives -- but also to think about how we use images and cultural materials to deepen our understanding and our research.

Many thanks to Dan Hammett for the t-shirt and image.